If your childhood included a milk crate of records in a Black household, you didn’t just hear the music—you inherited a living history of movement. Before you ever saw the steps, you knew the names: the Watusi, the Swim, the Jerk, the Pony. These dances mattered. DJ Sir Daniel and Jay Ray dive into this shared space, exploring how dances like The Twist connect Black generations from the past to the present.

The simple truth is this: in Black culture, music is inseparable from the body. For Gen X kids like Sir Daniel and Jay Ray, this history arrived through a mix of reruns—Soul Train lines on Saturday, What’s Happening!! routines, and even the “whitewashed” versions seen on shows like Gidget. This generational bridge allowed them to see both how Black families authentically moved at home and how white media packaged the music for mass consumption.

The Whitening of The Twist

The layered history of The Twist is central to this conversation. While most people grew up thinking of the song as belonging to Chubby Checker, the story truly begins with Hank Ballard, the Black artist who originally wrote and recorded the track for his group the Midnighters in 1958.

The song truly took off thanks to American Bandstand in 1960. But, host, Dick Clark and his team ultimately centered a new artist. Historical accounts suggest Ballard was either considered too “risqué” or simply unavailable. Regardless, Clark chose Chubby Checker, a singer who sounded similar to Ballard. The song was re-cut, the arrangement remained, but the face delivering it was deliberately changed. That is the version that became a national phenomenon.

Sir Daniel and Jay Ray dissect this moment, discussing the concept of “race records,” the systemic whitening of Black sounds, and the persistent fear of “Black magic” influencing white teenagers. The same cultural anxiety that led to Elvis being filmed from the waist up made Chubby Checker acceptable. The dance itself was also “safe,” allowing two people to move together without physical contact, which appeased nervous censors and anxious parents.

From Jim Crow to Hip Hop: The Dance as Archive

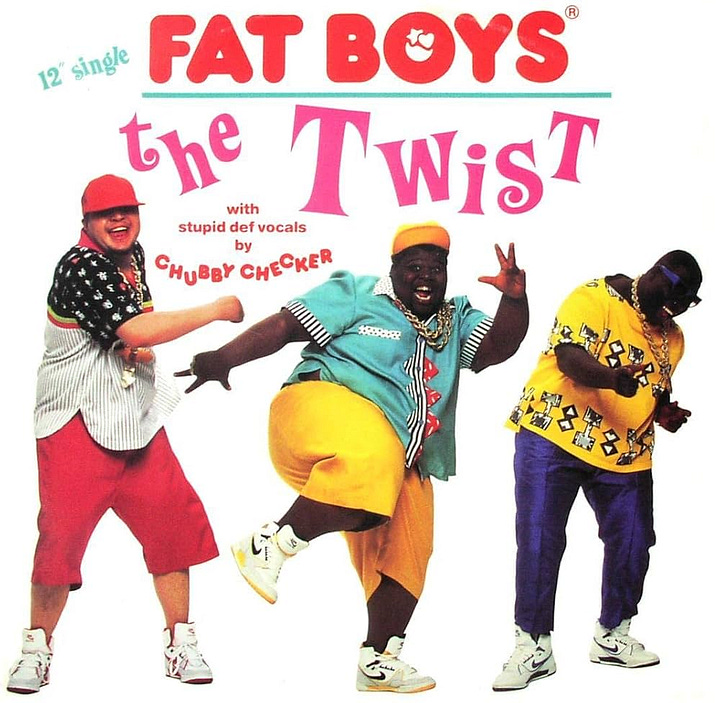

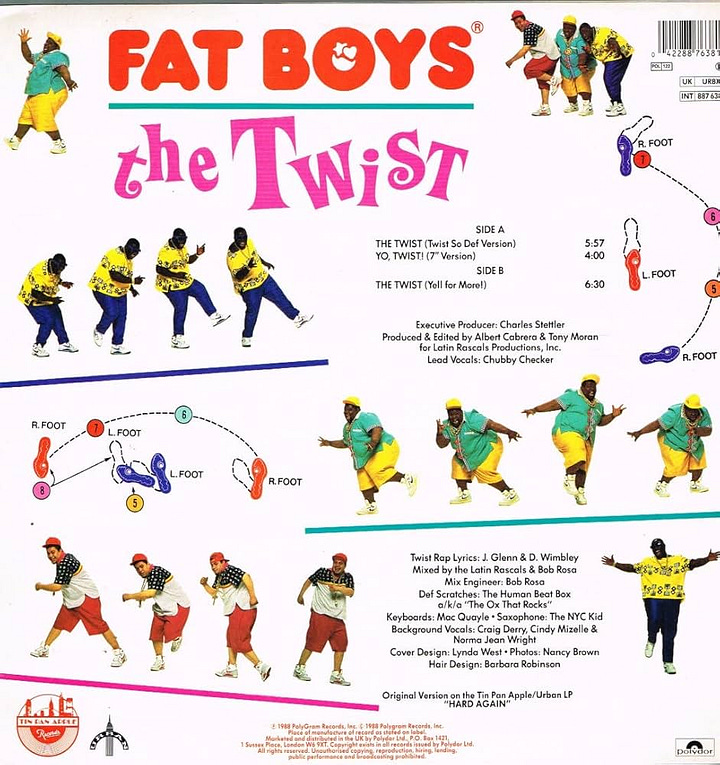

The story doesn’t end in the early 1960s. One of the most significant parts of the dance’s legacy is its return in the hip hop era. The Fat Boys, recognizing the power of nostalgia, sampled “The Twist,” pulling Chubby Checker and the foundational record back into rotation. Suddenly, a Black dance that helped carry their parents through the post–Jim Crow era was bouncing around breakdance clubs.

The conversation expands to the essential Bus Stop. Sir Daniel recalls an old clip of a local dance show in a Black city, where a host—an early MC—calls out the steps to the Bus Stop as People’s Choice’s “Do It Any Way You Wanna” plays. It was more than a dance; it was a snapshot of a scene: nightlife, Black style, local television, and community pride.

Jay Ray traces the Bus Stop’s migration from the West Coast eastward, eventually inspiring a dedicated track from Fatback Band. That track, in turn, was sampled later on Chaka Khan’s “Like Sugar,” keeping the groove alive for yet another generation. This is the pattern: a dance emerges from Black social spaces, a song attaches to it, and they combine to create a way for Black people to gather, move in sync at weddings, and celebrate.

Finally, the hosts circle back to the core idea: these dances are records, too. They form a living archive of how Black people celebrated and found joy during and after the intense political struggles of the 20th century. The hosts encourage listeners to not just learn the steps, but to ask their elders about those dance floors—and to document the TikTok routines and party dances of today, creating an archive for the future.